There is nothing that occurs in human life, from which he does not seek to extract some pleasure, although the matter may be serious in itself. If he has to do with the learned and intelligent, he is delighted with their cleverness, if with unlearned or stupid people, he finds amusement in their folly. He is not offended even by professed clowns, as he adapts himself with marvellous dexterity to the tastes of all. . . .

More was the author of Utopia, a novel which presented itself as the account of a journey an Englishman had taken to a strange land. He describes it to his correspondents, some of which are people More actually knew. By describing the realm of Utopia, More was able to obliquely discuss some of the social and political problems in Europe. Some of the concepts More introduces -- such as an abolition of private property, gender equality in education and employment, free healthcare, freedom of religion, and legalized divorce and euthanasia -- were hundreds of years before their time. It's no wonder More was one of the most respected intellectuals of his day.

He was born in 1478, son of Sir John More and Agnes Graunger. Sir John was a lawyer and a judge; Agnes was the daughter of an alderman of London. He attended school until he was old enough to join the household of the Archbishop of Canterbury, which taught him the refined manners expected in high society, and the inner workings of a noble home. He then attended Oxford, where he studied law.

For a time, More considered entering the church, which had to be an attractive prospect for a man of his piety. But he found the idea of celibacy too heavy a burden. As he put it, he decided he'd be better off as a faithful husband than a sinning priest. For a time, he lived in a Carthusian monastery, and the habits of worship and penance he acquired there would linger with him for the rest of his life. He kept to a strict level of religious devotion and was known to wear a hair shirt beneath his rich robes.

More became a member of Parliament in 1594, and from there, held a series of political positions before becoming one of the king's councilors in 1517. He was knighted in 1521. He moved up the ranks until he was the first non-churchman to hold the office of Chancellor.

The king found uses for his gifts as a writer, asking More to assist in writing Assertio Septem Sacramentorum. (Defense of the Seven Sacraments) an answer to Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses. Henry was given the title Defender of the Faith by the grateful pope, a title the king kept even after the break with Rome, and a title still held by the monarchs of Britain to this day.

More was given the task of responding to the crude and foul pamphlet Luther had written to refute Assertio and insult the king who wrote it. Under the pen name William Ross, More announced he could only respond in kind and so gleefully indulges in what one of his biographers calls a "satirical tour de force." More writes that since he had been commanded to "clean out the dungy writings of Luther like the Augean stable" he would go ahead and use the stuff the animals had left behind. And oh, fling shit he does! One wonders where he picked up such a colorful, creatively filthy vocabulary.

More married Jane Colt around 1505 and they had four children before she died in 1511. He quickly married again, this time to an older woman named Alice Middleton, herself recently widowed. More's friends had advised against it, because it seems Alice had a shrewish reputation, but More seems to have been very happy with her if his devotion to his family life is any indication. He's recorded as having laughed when someone asked him about his wife, and said she was not the most beautiful or charming of women, but More's playful, teasing manner made her very agreeable. He had no children with Alice, but he raised her daughter from her previous marriage as his own, and fostered other children.

|

| More and Erasmus meeting young Prince Henry and Princess Margaret Courtsey of http://www.explore-parliament.net |

More had decided to give his daughters the same classical education his son was given, and Meg, especially, excelled. She was so fluent in Greek and Latin that male scholars were impressed, even before they discovered she was female. The accomplishments of More's daughters helped change Erasmus's mind on the subject of female education. In turn, Erasmus's protégé Juan Luis Vives would write a book on the subject would open educational doors for women around the world.

More had once been Henry's friend-- or at least, as much of a friend as Henry could have. He used to drop by, unannounced, at the house in Chelsea to debate with More on theology and astronomy. Henry thought of More as a feather in his cap, that his court could brag of having one of Europe's finest minds walking its halls, and he respected that brilliant mind until the moment it came to a different conclusion than Henry wanted it to. More was under no illusions about Henry's "friendship." He told his son-in-law, William Roper, that if his head could win Henry a castle in France, off it would go.

More had once been Henry's friend-- or at least, as much of a friend as Henry could have. He used to drop by, unannounced, at the house in Chelsea to debate with More on theology and astronomy. Henry thought of More as a feather in his cap, that his court could brag of having one of Europe's finest minds walking its halls, and he respected that brilliant mind until the moment it came to a different conclusion than Henry wanted it to. More was under no illusions about Henry's "friendship." He told his son-in-law, William Roper, that if his head could win Henry a castle in France, off it would go.

More and his family had a warm and loving relationship, and indeed, they seem to me to be the happiest family among the Tudor nobility. He was immensely proud of his children’s intellectual accomplishments. While the parenting advice of the day suggested stern distance and harsh discipline, More employed gentle encouragement and reason in the raising of children. His daughters didn't want to leave even after they married, so their husbands moved into the house with them.

|

| Thomas More and his family, by Holbein Left to right: Elizabeth Dauncy (More's second daughter) Margaret Giggs Clement (adopted daughter) Sir John More (More's father) Anne Cresacre (young John More's fiancée) Sir Thomas More John More (More's only son) Henry Patenson (More family fool) Cecily Heron (More's youngest daughter) Meg More Roper (More's eldest daughter) Lady Alice More (More's wife) You can read bios of the pictured family members here. |

The household must have been a noisy one with so many people under one roof, the laughter of grandchildren and the sounds of the musical family all joining together for concerts in the evening. Holbein sketched the adults of his large household for a life-sized painting which, unfortunately, was never completed by him, though other artists painted it later, including a few versions which added in additional family members.

But More's own little Utopia was not to last. Henry VIII decided to annul his marriage to Katharine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn. Henry wanted More's public approval, for he said having More on his side would be worth more than the assent of half his kingdom.

Though More agreed that a king's marriage and his choice of heir should be the royal prerogative, he could not agree that the pope's dispensation was issued in error. In 1530, More refused to add his signature to a petition to the pope from the nobility and leading churchmen of England, asking for the annulment.

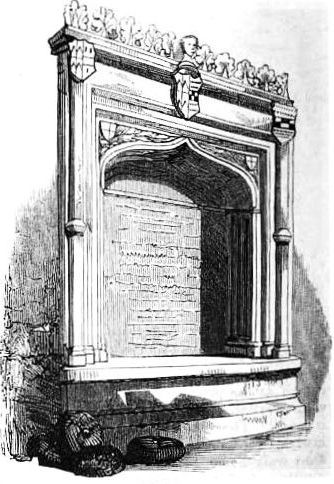

More attempted to resign as Chancellor when Henry broke with Rome because the pope wouldn't issue his annulment, but the king wouldn't let him go until More told him the stress of his position was causing him chest pains. Aware what his resignation would likely mean, More began building his tomb in Chelsea, including composing his own epitaph.

|

| More's tomb in Chelsea, which he never occupied. Courtesy of FindAGrave.com |

He didn't return to court for Anne Boleyn's coronation, which offended the king, and the councilors who had sent More money for new clothing. More shrugged and replied they wouldn't miss it-- they were rich. He was poor.

More never told anyone, except for the king, what he believed about the royal supremacy, and the validity of the king's marriage to Anne Boleyn. He famously said he would not even tell his wife. More, a trained lawyer, knew of the concept of qui tacet consentire: silence implies consent. The law held that a man who did not speak out against something would be counted as loyal. He could only be condemned for his words, for his actions.

Henry turned that law on its head with his Oath of Supremacy. Every male citizen was required to give the oath if asked, swearing that the king was the head of the church, his marriage to Anne was lawful and good, and the only heirs to the English throne would be Anne's children. More knew the commissioners would come to him eventually to ask him to swear. And he would not.

In April 1534, he was called before the commission at Lambeth, which was the house where he'd been sent as a lad to serve the archbishop. Usually, when he left to answer the council's summons, his family accompanied him down to the wharf. This time, he firmly shut the gate behind him, leaving his loved ones behind at the house. He confessed to his son-in-law, William Roper (Meg's husband) that he was afraid he would weaken for them, that his love for them and his desire to stay with his family would overcome his resolve to stand firm in his beliefs.

He took the barge up the river to Lambeth Palace, and More must have looked up at the window of the room he occupied as a child as he passed through the gate house. His judges included Anne Boleyn's father, and her brother, George Boleyn, and her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, king's officers, all, but it must have seemed to More like a Boleyn conspiracy at that moment. He was asked to swear the oath, and he refused, but said that he would speak nothing against it.

Richard Rich, the king's reprehensible solicitor general, stepped forward to give evidence and claimed More had confessed to him that he did not agree with the supremacy, that parliament could no more declare the pope was not head of the church than they could declare that God was no longer God. He must have thought More would remain silent in the face of his accusation. He was wrong.

More first spoke about Rich's credibility as a witness, in no uncertain terms:

|

| Richard Rich |

"You know that I have been acquainted with your manner of life and conversation a long space, even from your youth to this time; for we dwelt long together in one parish, where, as yourself can well tell (I am sorry you compel me to speak it), you were always esteemed very light of your tongue, a great dicer and gamester, and not of any commendable fame either there or at your house in the Temple, where hath been your bringing up."

He then denied he had confessed anything to Rich in equally unequivocal terms:

"[I]n good faith, Mr. Rich, I am more sorry for your perjury than mine own peril; and know you that neither I nor any one else to my knowledge ever took you to be a man of such credit as either I or any other could vouchsafe to communicate with you in any matter of importance."

It's doubtful anyone actually believed Rich over More. More had a pristine reputation for honesty and circumspection. Rich was known to be dishonest and corrupt. But in the end, it did not matter. More had refused to take the oath when asked, and according to the new law, he was guilty of treason. The judges gave him one last chance, sending him out into the garden to walk and think it over. More came back without having changed his mind.

He was put into a prison cell in the Tower. Nicholas Sanders, who wrote a history of the Reformation, never missed a chance to smear the memory of Anne Boleyn. He wrote that the king was going to forgive More and let him get away with only swearing the king's marriage was legal, but was nagged into harshness by Anne. But Henry never needed to be urged to be harsh when people refused to bow to his will.

More had once been Henry's friend-- or at least, as much of a friend as Henry could have. He used to drop by, unannounced, at the house in Chelsea to debate with More on theology and astronomy. Henry thought of More as a feather in his cap, that his court could brag of having one of Europe's finest minds walking its halls, and he respected that brilliant mind until the moment it came to a different conclusion than Henry wanted it to. More was under no illusions about Henry's "friendship." He told his son-in-law, William Roper, that if his head could win Henry a castle in France, off it would go.

More had once been Henry's friend-- or at least, as much of a friend as Henry could have. He used to drop by, unannounced, at the house in Chelsea to debate with More on theology and astronomy. Henry thought of More as a feather in his cap, that his court could brag of having one of Europe's finest minds walking its halls, and he respected that brilliant mind until the moment it came to a different conclusion than Henry wanted it to. More was under no illusions about Henry's "friendship." He told his son-in-law, William Roper, that if his head could win Henry a castle in France, off it would go.

More spent about a year and a half in the Tower as the king decided what to do with him. (He was likely hoping More would give in.) As he arrived, More teased the head jailer, who demanded the traditional payment of his topmost garment (his surcoat.) More plucked the hat from his head and handed it over, gravely informing him that the hat was the thing that was furthest at the top. He then pulled off his coat, probably still chuckling at the jailor's confounded expression.

At first, More seems to have been relatively content in the Tower. His lodgings were comfortable enough, for the era. Prisoners' families had to provide all of their furnishings, meals, clothes and medicines, even to pay to have their laundry washed and their chamberpot emptied. So, More had his own things with him, his books and writing materials, and modest comforts. He also had many visitors, for Henry sent many members of the court and highly-ranking churchmen to reason with More and try to get him to accept the supremacy. Meg persuaded the king to allow her to be one of them by writing her father a letter she knew her father's jailors would read, begging him to swear the oath. She was given permission quickly after that.

|

| Meg More Roper visiting her father |

He wrote a book while waiting for the king to decide his fate, and part of another, which ends in mid-sentence. When it was discovered he and Bishop Fisher, who had also refused the oath, had been writing letters of support to one another, encouraging each other to remain strong in their faith, More's books and writing paper was seized. No matter-- he wrote on scraps of paper smuggled to him by visitors, using charred wood from the fireplace for a pencil.

He was frequently visited by Meg, who brought him whatever she could to help make his life in prison more comfortable. His wife, Alice, also came to see him, but she wasn't quite as supportive as Meg. She couldn't understand why More would choose to sit in this dank, cold, rat-infested prison cell instead of being at liberty on his own estates. They supposedly had the following exchange, according to Nicholas Sanders' The Rise And Growth Of The Anglican Schism:

"And how long, my dear Alice, do you think I shall live?"

"If God will," she answered, "you may live for twenty years."

"Then," said Sir Thomas, "you would have me barter eternity for twenty years; you are not skillful at a bargain, my wife. If you had said twenty thousand years, you might have said something to the purpose; but even then, what is that to eternity?"

But despite her confusion and chiding words, Alice loved him. When his estates were seized upon More being sentenced to death, Alice sold her clothing to buy him food and comforts in prison.

More spent his trial with tongue firmly in cheek. He seems to have recognized there was no possibility of a verdict of "not guilty" and so he playfully confounded his judges, who expected pleading, not teasing. (Also from Sanders' Rise and Growth...)

In the course of his trial he was asked in court what he thought of the law--enacted after his imprisonment--by which the whole authority of the Pope was set aside, and by which the supreme power over the Church was vested in the king; he replied, that he did not know of any law of the kind.

The judge interposed and said, "But we tell you that such a law exists, what do you think of it?"

More replied, "If you treated me as a free man, I would have believed you on your word when you tell me that there is a law to that effect; but you have cut me off from your community, and you have shut me up in jail, not as a stranger but as an enemy. I am civilly dead; how is it that you question me concerning the laws of your state, as if I were still a member of the community?"

The judge lost his temper and said, "Now I see, you dispute the law, for you are silent."

Then said Sir Thomas, "If I am silent, that is to your advantage, and that of the law; for silence is consent."

"Then," said the judge, "do you acknowledge the law?"

"How can I do that," answered Sir Thomas, "seeing that no man can acknowledge anything of which he is ignorant?"

As expected, More was sentenced to die on the scaffold for his treason. Meg waited at the wharf to see him, correctly guessing they would have to bring him this way to be taken back to the Tower. When he was brought near, surrounded by armed soldiers, Meg burst through a line of guards, pushing past their halberds without a qualm. No one tried to stop her. She wept and kissed her father for the last time, and it's said the sight was so moving, the guards themselves wept.

More climbed the scaffold soon afterward, still joking. The scaffold was shoddily constructed, and so "merrily" he told the guards to help him up the stairs, but he'd shift for himself coming back down.

He said to the crowd that he died the king's good servant, but God's first. He recited a psalm, knelt and prayed. The executioner knelt in front of him and asked for forgiveness. More leaned forward and kissed him, and told the surprised executioner,

"Pluck up thy spirits, man, and be not afraid to do thine office. I am sorry my neck is very short, therefore strike not awry for saving of thine honesty [reputation]."

More tied a handkerchief around his own eyes and laid his head upon the block. Then, he suddenly gave a signal for the headsman to wait, and moved his beard out of the way. He said what are probably the strangest last words ever spoken: "Pity that should be cut. That has not committed treason."

More tied a handkerchief around his own eyes and laid his head upon the block. Then, he suddenly gave a signal for the headsman to wait, and moved his beard out of the way. He said what are probably the strangest last words ever spoken: "Pity that should be cut. That has not committed treason."

After those words, the axe fell, and one of the most brilliant lights in Europe was extinguished.

More had asked that his body be given to Meg to return home for burial near his family, or at least his wife and children be permitted to be present at his burial, but neither request seems to have been honored. Instead, he was tossed into an unmarked grave in the floor of the Tower chapel. Bishop Fisher, whose sad, naked corpse had been buried first in the nearby All Hallows Barking churchyard, was exhumed and buried next to More, to prevent people from stealing bits of his body as relics.

Sanders gives a different story, claiming More (who was later sainted) performed his first miracle at this point. Meg realized she hadn't brought a winding sheet for her father, and she had no money left to buy one. Her maid convinced her to go to the shop and pretend to search her empty purse for coins. She said the shopkeeper would take pity on the daughter of Thomas More and would let her have the winding sheet on credit. Meg went into the shop as her maid suggested, but when she felt in her purse for the money, the exact amount she needed for the linen suddenly appeared.

Sanders gives a different story, claiming More (who was later sainted) performed his first miracle at this point. Meg realized she hadn't brought a winding sheet for her father, and she had no money left to buy one. Her maid convinced her to go to the shop and pretend to search her empty purse for coins. She said the shopkeeper would take pity on the daughter of Thomas More and would let her have the winding sheet on credit. Meg went into the shop as her maid suggested, but when she felt in her purse for the money, the exact amount she needed for the linen suddenly appeared.

It's a nice story, but Meg was never given the chance to give her father burial rites. His body was taken from the scaffold straight into the chapel and buried unceremoniously. Indeed, the only executed person of this period I know of that was given any sort of last decencies is Anne Boleyn, and hers were paltry at best.

|

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons,

Photographed by Relee54

|

The Victorian excavation of the chapel floor was unable to identify Thomas More’s remains from among the other beheaded skeletons. In the 1970s, a memorial was built to Thomas More in the chapel, through a side door, closed to the public. It’s a rectangular monument of dark marble with a bust of More on the top. Engraved on the side are the words, Knight, Scholar, Writer, Statesman. I think More would have liked it.

After his execution, More’s head was placed on a pole on Tower Bridge, as was customary. According to legend, Margaret had them row her out in a boat under her father's head and she expressed a wish it would fall down into her lap, and PLOP! down the head came. A more mundane and realistic explanation is that Meg bribed a guardsman to get it down for her. (Truth be told, the council was thinking about getting rid of it anyway, because More and Fisher's heads were drawing crowds that clogged the bridge so badly traffic could not pass. People claimed the severed heads looked more lifelike every day, and birds would not peck at them. People were beginning to see it as a divine sign, and to call the two men saints.) Meg took the head home, where she preserved it with herbs and stored it in a lead box.

After his execution, More’s head was placed on a pole on Tower Bridge, as was customary. According to legend, Margaret had them row her out in a boat under her father's head and she expressed a wish it would fall down into her lap, and PLOP! down the head came. A more mundane and realistic explanation is that Meg bribed a guardsman to get it down for her. (Truth be told, the council was thinking about getting rid of it anyway, because More and Fisher's heads were drawing crowds that clogged the bridge so badly traffic could not pass. People claimed the severed heads looked more lifelike every day, and birds would not peck at them. People were beginning to see it as a divine sign, and to call the two men saints.) Meg took the head home, where she preserved it with herbs and stored it in a lead box.

The king's council found out about it and called Meg before them for "stealing" the head. She admitted to it readily, but for some reason, the council decided not to charge her with anything. She kept her father's head with her until her own death in 1544, when she was supposedly buried with it in her arms.

But the head’s journey doesn’t end there.

In 1835, the chapel of St. Dunstan's, home of the Roper vault, was being re-paved and those delightfully ghoulish Victorians went down into the Roper vault to see if they could find the head. They discovered it not in her coffin, as was expected, but within a niche in the wall. And, apparently, they let people down inside to take a peek whenever they liked, as the following article seems to demonstrate. (Historic UK says the skull was on display for many years.) It also demonstrates the attitude Victorians had toward antiquities and how they should be "restored."

Gentleman's Magazine, March 12, 1837

"As I have observed in your excellent Magazine, that a few years ago the public had taken a deep interest in the restoration of Sir Thomas More's monument in the Church of Chelsea, the place which was destined by the excellent and amiable man for the interment of his body, but which is in fact an empty cenotaph, I trust that less will not be felt by many of your readers for the spot where his head was placed; which was obtained (after its exposure on London Bridge) by his beloved daughter Margaret, and brought to her residence in St. Dunstan's, Canterbury, and deposited, by her request, in the same vault with her after her decease.

In the chancel of the church is a vault belonging to that family, which, is newly paving of the chancel, in the summer of 1835, was accidentally opened; and, wishing to ascertain whether Sir T. More's scull was really there, I went down into the vault, and found it still remaining in the place where it was seen many years ago, in a niche in the wall, in a leaden box, something of the shape of a bee-hive, open in the front and with an iron grating before it. In this vault were five coffins, some of them belonging to the Henshaw family, one much decayed, no inscription to be traced on it. The wall in the vault, which is on the south side, and in which the scull was found, seems to have been built much later than the time of Sir T. More's decapitation, and appears to be a separation between the Roper chancel and the part under the Communion Table.

[...]

In musing over these relics of days gone by, and connected as they are both above and below ground with that simple-minded an pious martyr, I could not but feel that I was treading on religious classic ground, and hope that a similar good feeling might induce some, who venerate the great and the good of other times, to manifest the same laudable wish to save from ruin the sacred walls which contain the head, as they have done in restoring the empty monument of that excellent man. I enter con amore into restorations of this sort, I have been planning how it might be done with best effect; and it has struck me that the eastern window of the chancel might be ornamented with a copy of that beautiful bust of Sir T. More by Holbein, and in the side lights might be placed the coats of arms of the different compartments by handsome small oaken beams, might be restored, and shields placed at the intersections of the angles; and a Gothic open screen of the same wood might surround the chancel. As a finish to the whole, I would have a handsome small vase of Bethersden Marble, standing on a plain circular pillar, erected under the window; in which I would place, if it was not thought improper, the scull itself, with a suitable inscription. But the difficulty is, HOW is all this to be accomplished? I see no other possible way, than some of the descendants of Sir Thomas paying this sacred debt (may I call it?) to the memory of their great and good ancestor, or by others not connected with the family, but who take a deep interest in matters of this sort; doing, in short, as your Magazine records they have been lately been doing at Chelsea, and paying the same mark of respect to the head in St. Dunstan's church, as they have there done to his empty tomb.

Note that the writer does not mention they were likely the one who broke open the bottom of the box to see if the "scull" was really inside. The writer partially got his wish. A nice set of stained glass windows featuring More and his family was installed, and a granite slab marking the spot of the vault was put in place in 1932, but alas, More's skull was not popped into a vase.

In 1978, the Roper vault below the church was re-opened for archeological excavation. There, they found a niche built into the brick wall with heavy bars built into the opening. Behind them was a lead box with a hole cut or broken into the side. Fragments of skull were visible through the opening, along with what appears to be white lead dust, perhaps used to whiten or preserve the skull. It’s believed this is the final resting place of the head of Thomas More.

No comments:

Post a Comment