Today, September 29, is the date on which Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio arrived in England, ostensibly to try the case of Henry's annulment petition and give Rome's ruling.

Today, September 29, is the date on which Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio arrived in England, ostensibly to try the case of Henry's annulment petition and give Rome's ruling.After young King Henry married Katharine, everything seemed like a fairytale for the royal couple. At the time, Henry was considered to be one of the most handsome princes in Christendom. He was tall with red-blonde hair and slate blue eyes, well-muscled, and athletic. He could be extremely charming... when he wanted to be.

The Venetian ambassador described him thus:

His Majesty is the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on; above the usual height, with an extremely fine calf to his leg, his complexion very fair and bright, with auburn hair combed straight and short, in the French fashion, his throat being rather long and thick. He was born on the 28th of June, 1491, so he will enter his twenty-fifth year the month after next. He speaks French, English, and Latin, and a little Italian, plays well on the lute and harpsichord, sings from book at sight, draws the bow with greater strength than any man in England, and jousts marvelously. Believe me, he is in every respect a most accomplished Prince; and I, who have now seen all the sovereigns in Christendom, and last of all these two of France and England in such great state, might well rest content.

Soon after their quiet wedding at Greenwich Palace, Henry and Katharine were crowned at Westminster Abbey amidst joyous celebration by the English people. The dual coronation ceremony was described by chronicler Edward Hall:

Inside, according to sacred tradition and ancient custom, his grace and the queen were anointed and crowned by the archbishop of Canterbury in the presence of other prelates of the realm and the nobility and a large number of civic dignitaries. The people were asked if they would take this most noble prince as their king and obey him. With great reverence, love and willingness they responded with the cry 'Yea, Yea'.

Henry had reputation for piety, attending mass at least four times a day. But Henry wasn't an attentive worshipper during services. Instead, mass was when he met with his ministers, signed documents, and did the tedious administrative work of his kingdom. Katharine was more legitimately pious. She rose for midnight mass and spent hours on her knees in daily prayer.

|

| Katharine the Quene |

Henry had received a somewhat unusual education for a prince. His father had intended him to be sent into the church once his brother had an heir, and so Henry was educated as a prelate, studying canon law and the scriptures. Had Arthur lived, Henry might have been a cardinal by this date.

When Henry came to the throne, he was staggeringly rich, one of the wealthiest monarchs in Europe. His father's careful management of money had amassed a tremendous fortune, and Henry decided to use it to raise the prestige of England in the sight of the world. The young king gathered from all corners of his kingdom the finest scholars, artists, and learned prelates. He brought a reluctant Thomas More to court, engaged the painter Hans Holbein, and set the finest architects in England to rebuilding or refurbishing his palaces.

Katharine was almost instantly adored by the court and commons alike. She was beautiful, regal, and gracious. Henry openly respected her intelligence, encouraging ambassadors to meet with her, and seeking her advice on policy decisions. He even took the unusual step of appointing her regent of England while he was out of the country, during which she ably handled an attack by Scotland which ended in the death of the Scottish king. Like her mother, Katharine rode out in armor, heavily pregnant, to rally the troops.

Henry and Katharine seemed like a happy, loving couple. He rode in jousts under the name Sir Loyal Heart, wearing Katharine's colors, and returned after the match to lay his prizes at her feet. He wrote her love songs and poetry, and their entwined initials "HK" adorned their palaces, and possessions. He wrote to her father and stated even if he were single, he would choose to marry her again. A song is attributed to Henry, found in his manuscript of music which contains the lyrics:

Pastimes of youth some time among

None can say but necessary.

I hurt no man, I do no wrong,

I love true where I did marry,

Though some say that youth rules me.

|

| The celebratory joust in honor of the new prince. King Henry rides a horse covered in letters "K" in honor of his wife. Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons |

She had another stillborn son before a healthy daughter was born, Princess Mary Tudor. While Mary was never officially granted the title of Princess of Wales, she was treated and educated as one. Compounding his doubts about his wife's ability to give him an heir, Henry's mistress, Bessie Blount, delivered a healthy bastard son, named Henry FitzRoy.

In all, Katharine had at least six pregnancies that ended in grief, possibly as many as ten. Her body was worn out from constant childbearing, and she became the wide, blocky figure we're familiar with in portraits.

In all, Katharine had at least six pregnancies that ended in grief, possibly as many as ten. Her body was worn out from constant childbearing, and she became the wide, blocky figure we're familiar with in portraits.As early as 1514, Henry had considered setting Katharine aside, according to the Duke of Buckingham. By the 1520s, he had more or less accepted he would have to in order to get the son he so desperately wanted.

In 1525, he took the surprising step of ennobling his bastard son, Henry FitzRoy, something that had not been done for centuries. But Henry not only gave the boy a title, he made him a duke twice over. FitzRoy was now six years old, the Duke of Richmond and Duke of Somerset. It looked like Henry was setting FitzRoy up as his heir, for the titles were ones traditionally held by princes in line for the throne.

Katharine was deeply unsettled by this, and was unwise enough to reproach the king. She had a healthy daughter able to step in as heir, after all. Katharine's mother, Isabella, had been a queen in her own right, ruling at her husband's side, and Katharine didn't see any reason why Mary couldn't take the English throne. Henry was angry about Katharine's protestations. To punish her, he ejected three of her favorite Spanish ladies in waiting from the court.

By 1527, Henry had a new reason for wanting to dissolve his marriage to Katharine. He had become enamored of a maiden at court, Anne Boleyn, but the bewitching girl refused to become his mistress, as her sister had done. If he wanted her--and he wanted her badly-- he had to marry her.

Henry thought it would be easy. To him, the reason for the annulment was perfectly clear: Katharine had been married to his brother, and Leviticus condemned a man who married his brother's widow, decreeing such a union would be childless. The pope had erred in issuing the dispensation; the pontiff could give permission to dispense with obeying church law, but not Scripture. A secret meeting was convened in which the obliging Wolsey charged the king with having an invalid marriage, and decreed that the case needed to be reviewed by the pope.

Henry told Katharine about the annulment himself. She had suspected that something was amiss, but not something of this magnitude. She burst into tears, and Henry assured her it was just a formality before he scampered from the room.

Katharine was a gracious lady, even when her heart was sore. She always treated Anne Boleyn with the utmost courtesy, pretending she knew nothing about the king's intention to marry her as soon as he could secure an annulment. Only one time is she ever recorded to have made an round-about reference to their situation, and the anecdote is likely apocryphal. George Wyatt wrote that during a game of cards, Anne drew a king. Katharine supposedly said:

My lady Anne, you have good hap to stop at a king, but you are not like others, you will have all or none.

It turned out Henry had the worst timing in the world. About the time he was gearing up to ask for an annulment, Emperor Charles V conquered Rome, and the pope became his virtual prisoner. Charles was Katharine's nephew, and he was not friendly to the notion his aunt had lived in sin for the last two decades. The pope could not issue an annulment that might anger his captor, so he did everything he could to stall the matter, hoping the king would tire of Anne or change his mind when the decree was not forthcoming.

The king's "Great Matter" was not popular with the people. Katharine had always been a beloved queen. The women of England saw the Great Matter as threatening the solidity of their own marriages. For if a man could set aside his lawful wife simply because he wanted another, where did that leave them? Some saw it as a bruise on England's prestige; a king should marry a princess, not a mere gentlewoman.

Henry saw his popularity plummeting, and so Edward Hall reports in that 1528, Henry hastened to assure his kingdom:

"For this only cause I protest before God and, in the word of a prince, I have asked counsel of the greatest clerks in Christendom, and for this cause I have sent for this legate as a man indifferent [unbiased] only to know the truth and to settle my conscience and for none other cause as God can judge.

And as touching the queen, if it be adjudged by the law of God that she is my lawful wife, there was never thing more pleasant nor more acceptable to me in my life both for the discharge and clearing of my conscience and also for the good qualities and conditions the which I know to be in her. For I assure you all, that beside her noble parentage of the which she is descended (as you all know) she is a woman of most gentleness, of most humility, and buxomness, yea, and of all good qualities appertaining to nobility, she is without comparison, as I this twenty years almost have had the true experiment, so that if I were to marry again if the marriage might be good, I would choose her above all other women.

But if it be determined by judgement that our marriage was against God's law and clearly void, then I shall not only sorrow the departing from so good a lady and loving companion, but much more lament and bewail my unfortunate chance that I have so long lived in adultery to God's great displeasure, and have no true heir of my body to inherit this realm. These be the sores that vex my mind, these be the pangs that trouble my conscience, and for these griefs I seek a remedy.

Therefore I require of you all as our trust and confidence is in you, to declare to our subjects our mind and intent according to our true meaning, and desire them to pray with us that the very truth may be known for the discharge of our conscience and saving of our soul, and for the declaration hereof I have assembled you together and now you may depart."

One wonders what Anne Boleyn thought, hearing that! Henry's deception and hypocrisy shows here, and in the fact he had asked the pope for a dispensation to marry a woman whose sister had been his mistress. According to canon law, it created the exact sort of affinity Henry was arguing couldn't be erased by a dispensation.

|

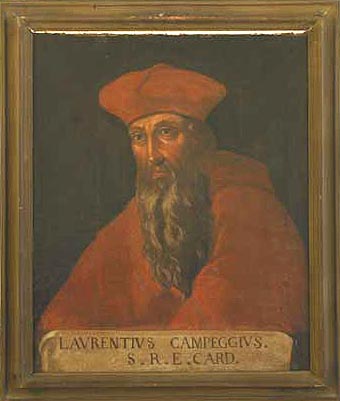

| Cardinal Campeggio Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons |

The case dragged on for seven years. Cardinal Campeggio arrived in England as the pope's representative, but it was mostly as a stalling technique. An old and frail man, it took him ages to travel to England and to recover from the trip. One of the first things he did was give Katharine a message from the pope, pleading with her to become a nun, which would automatically end the marriage. Katharine refused. Campeggio wrote about it in his report to Rome:

The queen stated that she had heard that we were to persuade her to enter some religious house. I did not deny it and constrained myself to persuade her that it rested with her, by doing this, to satisfy God, her own conscience, the glory and fame of her name, and to preserve her honours and temporal goods and the succession of her daughter.

I begged her to consider the scandals and enmities which would ensue if she refused. On the other hand, all these inconveniences could be avoided. She would preserve her dower, the guardianship of her daughter, her rank as princess, and, in short, all that she liked to demand of the king; and she would offend neither God nor her own conscience.

After I had exhorted her at great length to remove all these difficulties, and to content herself with making a profession of chastity, setting before her all the reasons which could be urged on that head, she assured me she would never do so: that she intended to live and die in the estate of matrimony, into which God had called her, and that she would always be of that opinion, and would not change it. She repeated this many times so determinedly and deliberately that I am convinced she will act accordingly. She says that neither the whole kingdom on the one hand, nor any great punishment on the other, even though she might be torn limb from limb, should compel her to alter this opinion. I assure you from all her conversation and discourse, I have always judged her to be a prudent lady. But, as she can avoid such great perils and difficulties, her obstinacy in not accepting this sound counsel does not much please.There was a hearing at Blackfriars on the validity of the marriage. It was Katharine's one chance to present her case to Henry, the papal court, and the world, and she knew it. She came prepared with a speech, not a legal brief. She entered the courtroom, ignoring the caller, and walked straight to where her husband was sitting. Katharine cast herself on her knees and pleaded with her husband.

“Sir, I beseech you for all the love that hath been between us, and for the love of God, let me have justice. Take of me some pity and compassion, for I am a poor woman, and a stranger born out of your dominion. I have here no assured friends, and much less impartial counsel…The point Katharine made here about Henry and Katharine having "divers" (many) children, though they all died, is an important one. Henry's case hinged on the Levitical curse, that a man who married his brother's widow would be childless. They weren't. They had a daughter, a healthy and intelligent girl, who was fully capable of being England's heir.

"Alas! Sir, wherein have I offended you, or what occasion of displeasure have I deserved?… I have been to you a true, humble and obedient wife, ever comfortable to your will and pleasure, that never said or did any thing to the contrary thereof, being always well pleased and contented with all things wherein you had any delight or dalliance, whether it were in little or much. I never grudged in word or countenance, or showed a visage or spark of discontent. I loved all those whom ye loved, only for your sake, whether I had cause or no, and whether they were my friends or enemies. This twenty years or more I have been your true wife and by me ye have had divers children, although it hath pleased God to call them out of this world, which hath been no default in me… "

"When ye had me at first, I take God to my judge, I was a true maid, without touch of man. And whether it be true or no, I put it to your conscience."Henry did not answer this. According to some accounts, he couldn't even look at her. He never made a personal statement about Katharine's virginity-- or lack thereof-- on their wedding night. He had witnesses to claim Arthur was capable of sexual intercourse, the number of times he visited

Katharine's rooms, and his boasts about being in the "midst of Spain," but Henry never said anything about what he had experienced when he first lay with Katharine. Maybe he was unable to directly call her a liar. Or, perhaps, as historical fiction author Margaret George has suggested, Henry was so inexperienced himself, he was unable to tell.

"If there be any just cause by the law that ye can allege against me either of dishonesty or any other impediment to banish and put me from you, I am well content to depart to my great shame and dishonour. And if there be none, then here, I most lowly beseech you, let me remain in my former estate… Therefore, I most humbly require you, in the way of charity and for the love of God – who is the just judge – to spare me the extremity of this new court, until I may be advised what way and order my friends in Spain will advise me to take. And if ye will not extend to me so much impartial favour, your pleasure then be fulfilled, and to God I commit my cause!”

She then rose to her feet and headed for the door. The caller demanded she return, but Katharine called back that this was no impartial court, and she would not linger. Campeggio, unable to stall any longer on giving a verdict, referred the case back to Rome. Henry was furious, and nothing was more dangerous than Henry when he was seeking a target for his frustrated anger.

Anne Boleyn, who may have borne a grudge against Wolsey for the heavy-handed way he had dealt with her betrothal to Henry Percy, felt Wolsey wasn't trying all that hard to annul the marriage, for then his enemy, Anne, would be queen, and she wasn't likely to treat Wolsey with generosity. The king became inclined to agree, especially when it appeared Wolsey might be engaged in treasonous activities. Wolsey died on his way back to court to answer these charges.

In 1529, Anne Boleyn gave Henry a book by William Tyndale, The Obedience of the Christian Man, which set forth the notion that kings were God's representatives on earth, answerable only to Him, not to the pope. Henry very much liked the idea he was answerable to no one. It wasn't long before he began to systematically dismantle England's ties to Rome, with the help of Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Henry secretly married Anne Boleyn in either late 1532 or early 1533. At Easter, Cranmer declared Henry's marriage to Katharine null and void, and his marriage to Anne Boleyn legitimate and good. Katharine was ordered to stop using the title of Queen of England.

Katharine refused to obey, which must have been difficult for a woman conditioned to obey from childhood. But obeying would mean lying in Katharine's eyes, lying and saying her marriage wasn't valid. She said such a lie would damn her soul, and so she would not agree to it.

Aside from the dynastic aspects, there may have been emotional ties which compelled Katharine to cling to her marriage. From all appearances, she still loved Henry, though he was no longer that pious, handsome prince she had married. She was certain he would one day see the truth and return to her. She just had to wait, as she had waited after the death of her first husband. And endure.

Katharine was exiled from court, separated from her daughter, and sent from house to house among Henry's little-used manors. Though she was forbidden to have contact with Mary, she managed to send letters to her daughter, urging her to remain strong in her faith, and assuring her of her other's love. Katharine had always been very close to her daughter, unusual in an age where royal children were raised by others and sent away to marry as soon as physically possible. The separation was agonizing for both of them.

Henry treated both his ex-wife and daughter with increasing cruelty, trying to force them into accepting the annulment and their new titles. Neither would break. He separated Katharine from her friends, her family, her familiar surroundings. He took her jewels for Anne, ordered her to stop sending him Christmas gifts, and to stop making him shirts, as she had always done. Bit by bit, he took everything she loved from her, and she spent her last years in sad exile.

It wasn't all Henry's doing, of course. The break with Rome was as much Katharine's doing as it was Henry's. Her refusal to consider entering a convent or agreeing to annul her marriage pushed him to up the stakes. After twenty years, Katharine knew Henry was not one to be denied anything he wanted, no matter what he had to do to get it. Her beloved daughter was stripped of her rights, regardless of her mother's refusal to agree to the annulment.

It wasn't all Henry's doing, of course. The break with Rome was as much Katharine's doing as it was Henry's. Her refusal to consider entering a convent or agreeing to annul her marriage pushed him to up the stakes. After twenty years, Katharine knew Henry was not one to be denied anything he wanted, no matter what he had to do to get it. Her beloved daughter was stripped of her rights, regardless of her mother's refusal to agree to the annulment.Since Katharine refused to speak to anyone who did not address her as queen, she remained sealed in her chambers, seeing only officers of the king, sent to try to badger her once more into submission. Katharine became convinced Anne Boleyn was trying to poison her, and so she would only eat food prepared by her ladies in her presence, cooked over the fire in her chambers. Katharine of Aragon, daughter of the "Catholic Kings" had been reduced to hiding in her chamber, eating like a peasant.

She was still a very wealthy woman, but she did not live in the kind of pomp and splendor to which she was accustomed. Some of the houses were in ill repair and drafty. Katharine's health suffered for it. She died on January 7, 1536. Anne Boleyn would follow her to the grave just a few months later.

It had been agreed upon beforehand that right before she received her last communion, Katharine would swear on the host that she had been a virgin when she married King Henry. It was supposed to be her last-ditch effort to save her daughter's rights. But, for some reason, the vow was never made. Did she simply forget? Did it not seem important in the last moments of her life? Or-- at this very last-- did she not want to meet her maker with a lie on her lips?

Before she died, she supposedly wrote one last letter to the man who had been her husband for a quarter of a century. Scholars doubt its authenticity, because it doesn't enter the historical record until much later, but I think it's worth including, because it's what Katharine should have said to Henry, even if she didn't.

My most dear lord, king and husband,

The hour of my death now drawing on, the tender love I owe you forceth me, my case being such, to commend myself to you, and to put you in remembrance with a few words of the health and safeguard of your soul which you ought to prefer before all worldly matters, and before the care and pampering of your body, for the which you have cast me into many calamities and yourself into many troubles.

For my part, I pardon you everything, and I wish to devoutly pray God that He will pardon you also. For the rest, I commend unto you our daughter Mary, beseeching you to be a good father unto her, as I have heretofore desired. I entreat you also, on behalf of my maids, to give them marriage portions, which is not much, they being but three. For all my other servants I solicit the wages due them, and a year more, lest they be unprovided for.

Lastly, I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things.

Katharine the Quene.

Her embalmers found a black growth on her heart. At the time, they felt it was a sign of poison, but it was most likely a cancerous growth. In the end, Katharine literally died of a broken heart.

Katharine's funeral was given the level of ceremony due a princess dowager, not an ounce more. During her funeral, the preacher said she had finally admitted she was never Henry's true wife. Henry's last ditch-effort, too, I suppose.

|

| Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons |

She was buried in Peterborough Cathedral in as simple a tomb as Henry could decently provide. In the late Victorian era, it was renovated to restore her title to her: KATHARINE QUEEN OF ENGLAND.

No comments:

Post a Comment