Sir Francis Bryan was a wiley soul. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he always kept the favor of Henry VIII, probably because of his smooth ability to change his opinions to suit those of the king's. This lack of principles and his dissolute lifestyle gave Bryan the nickname, "The Vicar of Hell."

Sir Francis Bryan was a wiley soul. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he always kept the favor of Henry VIII, probably because of his smooth ability to change his opinions to suit those of the king's. This lack of principles and his dissolute lifestyle gave Bryan the nickname, "The Vicar of Hell."Bryan was born around 1490 and was a second cousin of both Anne Boleyn and Jane Seymour. His mother, Lady Bryan, had been a lady in waiting to Queen Katharine and was a governess for Princess Mary Tudor. Francis Bryan was also the brother-in-law of Nicholas Carew.

In 1519, Bryan and Carew were sent on a diplomatic mission to Paris. He and Carew joined with the French courtiers who rode through the streets in disguise while throwing eggs and stones at commoners. When Carew and Bryan returned to England, they retained their sophisticated French style and mocked the clothing and habits of the English courtiers. Not surprisingly, he was one of the gentlemen cut from the king's service when Cardinal Wolsey re-organized the king's household later that year. Wolsey said Bryan and other young courtiers, "were so familiar and homely with [the King], and plaied suche light touches with hym that they forgat themselves..."

Robert Hobbes, a friend of Bryan's noted, "Sir Francis dare speak boldly to the king’s Grace the plainness of his mind and that his Grace doth well accept the same." Still, Bryan was always canny enough to make sure that speech was whatever Henry wanted to hear at the time.

Henry once used Bryan's bold speech to test his daughter, Mary. The king, despite knowing how sheltered his daughter was, couldn't believe she was truly as innocent and ingenious as she seemed. He sent Bryan over to say something filthy to her to see how she would react. Mary didn't get it.

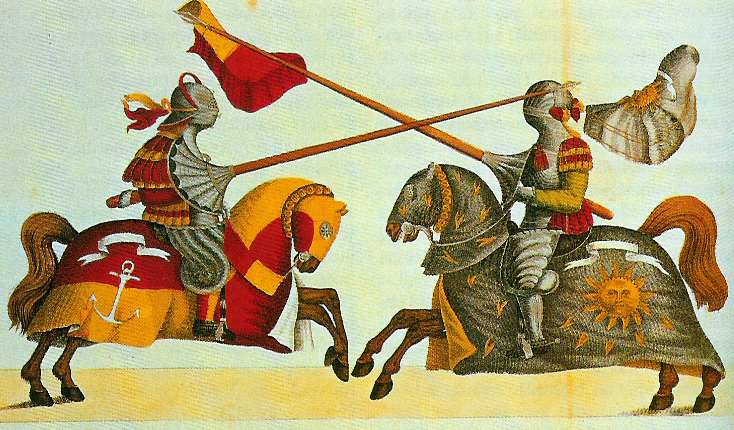

Bryan found his way back to court, and was put on a reduced, revolving schedule with other courtiers when the new household ordinances (the ones that also banned large dogs from the palace) were created. In 1526, Bryan competed in a jousting tournament and lost an eye. The chronicler Edward Hall wrote:

|

| Source: Wikipedia Commons |

This yere the kyng on Shrouetewesdaie, kept the solemne Iustes at his Manour of Grenewiche, he hymself and xi wer on the one part, and the Marques of Excester with xi wer on the other parte: At this Iustes was many a spere broken, and by chaunce of shiuerying of the spere, Sir Francis Brian lost one of his iyes.

He wore an eyepatch afterward. According to family legend, this is why no portrait of Bryan exists; he didn't want to be pictured with an eyepatch.

When Mary Boleyn's husband, William Carey died, Bryan stepped in to fill the vacancy Carey left in the privy chamber. It's thought that perhaps Anne Boleyn influenced the king to give the position to her cousin. He held various positions throughout his life at court and became a wealthy man in the king's service. He seems to have been somewhat of a jack-of-all-trades, able to handle both diplomatic and practical tasks with aplomb. Despite his nickname and reputation for debauchery, Bryan seems to have had a friendly, easy-going nature, though he was always careful to stay on the king's good side with his alliances, quickly distancing himself from positions and people who lost favor.

Bryan was a poet of some renown, and translated literary works into English. He was said to have been educated at Oxford. He was a contributor to the books of poetry which circulated in the court, though today, we do not know which works are his. He may be the "Brian" to whom Erasmus refers as one of his correspondents.

Bryan was a poet of some renown, and translated literary works into English. He was said to have been educated at Oxford. He was a contributor to the books of poetry which circulated in the court, though today, we do not know which works are his. He may be the "Brian" to whom Erasmus refers as one of his correspondents.Bryan must have been a smooth talker because he was the one the king sent to Rome to speak personally to the pontiff about his annulment suit. After convincing the pope to sign off on it, Bryan was supposed to urge the pope to withdraw his friendship from the Emperor Charles. (The emperor was not pleased Henry was--in essence-- insisting Charles's aunt, Katharine, had lived in sin with Henry for twenty years and produced a bastard daughter, to whom Charles had once been betrothed.)

Bryan wrote to Anne Boleyn and told her to expect an end to the waiting soon, and he wouldn't write to her again until he had good news. He would convince the pope to allow her marriage to the king. Six months later, he had to write to her and confess he hadn't been successful. Despite his failure, he remained a favorite of the king and was sent on other diplomatic and political missions relating to the king's marriage plans. Arriving in Marseilles, he sent a letter to his friend Lord Lisle, saying that after drinking the wine in Marseilles, on his return to Calais, he wished Lisle would prepare for him a soft bed, rather than a hard harlot. Lisle apparently replied in the same humorous vein he could provide both.

After the king married Anne, Bryan was riding high. He had the favor of the king and the status of

being the cousin of the queen. He had a reputation for womanizing, drinking, gambling, and rich, ornate clothing, and was rumored to help Henry make arrangements with women he wished to seduce. The latter is likely a falsehood, because Henry was never much of a womanizer; he married most of the women he slept with. We know of only two confirmed mistresses, Bessie Blount and Mary Boleyn.)

When Anne Boleyn began to lose favor with Henry, Bryan began to distance himself from the Boleyn family, including possibly inventing a quarrel with George Boleyn to give the king an excuse to distance himself, as well, by "siding" with Bryan. He began to support the Seymour family's efforts to push Jane toward the throne. Nicholas Carew, Bryan's brother-in-law, was one of Jane's biggest supporters. He coached Jane on how to behave to keep the king's interest.

|

| Thomas Cromwell |

Sir Francis Bryan, the queen's cousin, was at first suspected. He was absent from the court, and received a message from Cromwell to appear instantly on his allegiance. The following extract is from the Deposition of the Abbot of Woburn — MS. Cotton. Cleopatra, E iv.:

"The said abbot remembereth that at the fall of Queen Anne, whom God pardon, Master Bryan, being in the country, was suddenly sent for by the Lord Privy Seal, as the said Master Bryan afterwards shewed me, charging him upon his allegiance to come to him wheresoever he was within this realm upon the sight of his letter, and so he did with all speed. And at his next repair to Ampthill, I came to visit him there, at what time the Lord Grey of Wilton, with many other men of worship, was with him in the great court at Ampthill aforesaid. And at my coming in at the outer gate Master Bryan perceived me, and of his much gentleness came towards meeting me; to whom I said, "Now welcome home and never so welcome."

He, astonished, said unto me, "Why so?"

The said abbot said, "Sir, I shall shew you that at leisure," and walked up into the great chamber with the men of worship.

And after a pause it pleased him to sit down upon a bench and willed me to sit by him, and after that demanded of me what I meant when I said, "Never so welcome as then;" to whom I said thus: "Sir, Almighty God in his first creation made an order of angels, and among all made one principal, which was the [devil], who would not be content with his estate, but affected the celsitude and rule of Creator, for the which he was divested from the altitude of heaven into that profundity of hell into everlasting darkness, without repair or return, with those that consented unto his pride. So it now lately befell in this our worldly hierarchy of the court by the fall of Queen Anne as a worldly Lucifer, not content with her estate to be true unto her creator, making her his queen, but affected unlawful concupiscence, fell suddenly out of that felicity wherein she was set, irrecoverably with all those that consented unto her lust, whereof I am glad that ye were never; and, therefore, now welcome and never so welcome, here is the end of my tale."

And then he said unto me: "Sir, indeed, as you say, I was suddenly sent for, marvelling thereof and debating the matter in my mind why this should be; at the last I considered and knew myself true and clear in conscience unto my prince, and with all speed and without fear [hastily set] me forward and came to my Lord Privy Seal, and after that to the King's Grace, and nothing found in me, nor never shall be, but just and true to my master the King's Grace."

And then I said, "Benedictus, but this was a marvelous peremptory commandment," said I,"and would have astonished the wisest man in this realm."

And he said,"What then, he must needs do his master's commandment, and I assure you there never was a man wist to order the king's causes than he is; I pray God save his life."

The language both of Sir Francis Bryan and the abbot is irreconcilable with any other supposition, except that they at least were satisfied of the queen's guilt.

|

| Jane Seymour |

on the scaffold. Her reaction is not recorded. His friendly support of Jane was well-rewarded. In a letter from Cromwell to Stephen Gardiner, dated May 14, 1536, Cromwell primly denounces Anne’s horrible deeds and in the next sentence, starts divvying up the salaries and pensions of the condemned:

“…I write no particularities; the things be so abominable that I think the like was never heard. Gardiner will receive 200£ of the 300£ that were out amongst these men, notwithstanding great suit has been made for the whole; which though the king’s highness might give in this case, yet his majesty does not forget your service; and the third 100£ is bestowed of the Vicar of Hell upon [whom], though it be some charge unto you, his Highness trusts you will think it well bestowed.”About a year after Anne Boleyn's death, Bryan was sent to France to kidnap Cardinal Reginald Pole and bring him back to England so Henry could punish him for his denunciation of Henry's annulment suit, and his support of the excommunication which invited foreign princes to conquer England. Some believe that Bryan may have warned Pole instead, allowing the cardinal to "escape." Infuriated at being thwarted, the punishment fell on Pole's family instead.

The instructions he was given sometimes pained Bryan. After the death of Jane Seymour, Henry wanted to make a dynastic marriage to give England strong allies in the face of the ever-shifting alliances of the continent. But he would not marry just any woman. He wanted to see her first. To say that such a stance was bizarre is an extreme understatement. It simply was not the way royal marriages worked. But Henry had never cared about defying the social order, customs, or traditions and he didn't see why everyone shouldn't see him as an exception.

He instructed Bryan to ask if Marie de Guise and some French noblewomen could be sent to him to look over and pick the one he liked best. Bryan obediently posed the question, though he must have been inwardly cringing. And it was probably no surprise to him that he was treated with cool hostility after asking.

But Henry was offended and upset at the refusal. He complained to the French ambassador, who wryly asked if he'd also like to "....would perhaps like to try them all [have sex with them], one after the other, and keep for yourself the one who seems the sweetest?" Henry had sufficient grace to be abashed, but he insisted Bryan make the request again a bit later. Since King Francis was coming to Calais soon, he should have the queen bring seven or eight young women of royal lineage for Henry to inspect. Francis replied (with what one must imagine was icy royal dignity) that it was not the custom of France to trot out princesses like hackneys for sale.

|

| "God's bones, Harry, will you just pick one already?" |

Bryan ended up as one of the men sent to meet Anna von Kleefes when she arrived in England, and only a few years later, he was one of the officers of Henry's funeral. He entered young King Edward VI's service, but his career had reached its zenith with the king's death.

In 1548 Bryan married the very fecund Lady Joan Fitzgerald, the mother of seven sons, who had recently been widowed. Her husband James, Earl of Ormonde--who had once unsuccessfully negotiated for the hand of Anne Boleyn at the urging of the king-- died after being poisoned. His death, oddly enough, wasn't much investigated. Lady Joan intended to marry again, this time to a Fitzgerald relative, which would unite two great Irish houses. To prevent this union and the political power it would create, Bryan was asked by the council to marry Lady Joan himself, and was created lord marshall of Ireland for his pains. He had three children with her.

Bryan died suddenly in 1550. His last words were supposedly: “I pray you, let me be buried amongst the good fellows of Waterford (which were good drinkers).” An autopsy was unable to determine a cause of death.

No comments:

Post a Comment